The false nine from Brazil 1970 evokes the futuristic performance of the most legendary national teams of all time.

Note: This is a translation of an article written by DIEGO TORRES for El Pais in June of 2020. It has been translated here from Spanish for educational, non-commerical purposes only

Eduardo Gonçalves de Andrade, alias Tostão, is an ophthalmologist. For almost half a century he has been living a practically anonymous live in Belo Horizonte, the city where he was born in 1947. But when he picks up the phone and I mention the 1970 World Cup, the genial strategist of the most legendary national team in the history of football can remember every detail without effort, as if all the protagonists were still alive and time had stopped at the referee’s final whistle, on July 21st, half a century ago at the Azteca Stadium.

Question. Why has that selection of players left such an indelible mark?

Answer. Because of the combination of individual talent with collective talent that is the basis of organized football, tactically disciplined. We were coming from an era in which football was really disconnected: Defense, Midfield, and attack were not always acting in a synchronized form. Teams stood out for their isolated attacks and in this world cup we saw a more collective football. That choral harmony was combined with the fantasy and individual capabilities of the players. The other important detail is that we were a team that was as revolutionary in our physical preparation as we were with our game strategy. In the second halves of those games, Brazil always played better than in the first halves, and managed to score more goals. Another detail was the problem of altitude. (Mexico City finds itself at 2500 meters above sea level) We prepared with a very scientific formula. From this methodological point of view, Zagallo was a coach who strayed from the normal pattern, because in Brazil the coaches had little importance. The players solved the problems. But Zagallo was a strategist. Every day he liked to insist on training sessions that modified the behavior of the players in different phases of the game, in defensive and offensive positioning. Today everybody talks about this. But at the end of the ‘60’s this was not common.

Q. What was the big tactical innovation?

A. For the first time in the history of Brazil, the 1970 team was a compact team: when we lost the ball we all marked, starting from the midfield and working backwards, in order to close the spaces of our opponents. There were improvised actions, but the functionality was collective. When our rivals entered our half of the field, we battled a lot. This was not common back then. This is what we see now. And when we recovered the ball we went forward quickly, either interchanging passes or with long passes, especially to Jairzihno, who had incredible pace and physical strength. Brazil’s play was comparable with a great team from the 21st century. When we scored the goal to make it 2-1 against Uruguay, all of the Brazilian players were defending in our half. Jairzihno took advantage of an error by Fontes and played a pass to Pelé in the center circle. Pelé laid off a touch to me and I gave a pass back to Jairzihno who scored with a shot to the far post. We played with counterattacks and rapid touches. After the World Cup in Russia they made a comparative study of the National Teams of 2018 and 1970. Brazil of 1970 made more passes, dribbled more, shot more, and stole more balls from opponents! How could what we did not make an impression?

Q. There was a coaching school in Spain that gave lectures on our offensive throw-ins. The 1-0 goal against Italy in the final was scored in part thanks to your throw-in… Were these details really relevant?

A. The tendency is prejudice. Not just in football, but in life in general. We are inclined to judge that improvisation does not fit with structure. We say that the creative players are not organized and not disciplined, that the hard working players can’t give good passes. In all professions the creative people are separated from the pragmatic. When you unite these two things, when you combine utility and fantasy, great things emerge. The geniuses are never one dimensional.

Q. The legend says that the scheme was a 4-2-4 with Gerson and Clodoaldo in the midfield. And the front line is recited as: Jairzinho, Tostão, Pelé and Rivelino. What is the myth and the reality of this 4-2-4?

A. It was more of a 4-3-3 because Rivelino, Gerson and Clodoaldo formed a line of three midfielders. Jairzinho, Pelé and I moved up front, but interchanged positions a lot. Jairzinho managed to be a winger and a center forward. Pelé dropped back to receive the ball, but a lot of times he played on the left as a winger. Rivelino interchanged between the left wing and the midfield. The mobility was very high from a tactical reference point. Before the World Cup, at Cruzeiro, I played as the point midfielder and organizer. At the World Cup I had to improvise as a center forward. Rivelino at Corinthians played in Gerson’s position, the volante, and at the World Cup we moved him to the left. At Botafogo Jairzinho was the center forward and in Mexico he played as a winger. We made changes to fit the characteristics of the players, uniting one quality with another, completing each other on the field. A lot of times a team can play for a year without becoming a great ensemble. But for art and magic, in a small amount of time we came together to create an exceptional collective and individual game.

Q. In Mexico, you looked as if you had goal scoring in your blood. How was your conversion to a number 9?

A. At Cruzeiro, I played in Pelé’s position, I was a number ten goal scorer. I was moving a lot from one transition to another, I was in all the positions, I was getting in the area, getting forward, creating goals, dropping back. So I adapted with the National Team as a center forward. To play alongside Jairzinho and Pelé, two extremely aggressive players… gunners, always ready to go… it was necessary to understand that they needed a third man who was more inclined to pass the ball, to touch the ball first. For them I was a facilitator. When Zagallo assumed the role of selector in 1967, he was thinking that I was the heir to Pelé, and not that I would be at his side, because we overlapped each other. He wanted Dadá, a typical center forward, the kind who waited for the ball and shot. Afterwards, in 1970, Zagallo called me and said: “Can you play in front of Pelé, without coming back much, like you do in Cruzeiro?” “Not a Problem.” I told him. “I am going to play like Evaldo at Cruzeiro, He is a facilitator who moves in the area. He helps me to arrive with clarity. I can do the same with Pelé and Jairzinho in the National Team.”

Q. What do you need to be a good facilitator?

A. Play with one touch. Two at the maximum. When the ball hits you, you have to know where your team mates are. Rapidly. The game cannot stop. If you control the ball and stop, the game stops and the defense closes the spaces. This was one of my characteristics. At Cruzeiro I played one touch a lot. When I arrived at the National Team, once during a game Gerson came to me and said “Hey, play with two touches instead of one, because this will give me time to arrive in position.” I told him “Fine. With Pelé and Jairzinho, I will play with one touch. With you, I’ll play with two.”

Q. Today, with the spaces always being reduced, the teams that want to attack always need to play one touch….

A. Firmino at Liverpool is the facilitator for Mané and Salah. They are very fast and Firmino moves in the midfield playing very fast so that Mané and Salah arrive at goal at speed. It’s more or less how we played with Jairzinho and Pelé. For me, Firmino always gives me the impression that he is always playing with fast touches, the way extremely cognitive players do.

Q. How has your first encounter with Pelé?

A. Before the World Cup 66, I was 19 years old. In the friendlies, I was the backup for Pelé. Everybody was considering me the backup for Pelé because I played the same position: I dropped into the midfield to receive the ball, like Pelé did… I was not the kind of player to be close to the goalkeeper. For years I was the replacement for Pelé. During the qualifiers of ’69 the selector, Joao Saldanha, told me: “You are going to play alongside Pelé”. Those qualifiers were the best moments in my entire career with the National Team. We understood each other very well. Because Pelé, before the ball arrived to him, when he received it from Gerson or Rivelino, started to move and to look at me. Like saying: “Pay attention to what I’m going to do.” It required maximum concentration. Before the ball arrived, he was already urging you. He was so intelligent that keeping up with his reasoning required you to be very fast. When Zagallo saw us he changed his opinion and decided we would play together at the World Cup.

Q. When you define the virtues of Pelé, above all you mention his passing ability. Aren’t goals the most valued quality for a

footballer? And the feints that Pelé did, like the one he put on Mazurkiwicz?

A. Football is passing. One of the principle problems of Brazilian football is that for the last 20 or 30 years, the pass has been valued less and dribbling and scoring goals has been overvalued. So, the great maestros of the ball, the great players, the great thinkers in the midfield, like Gerson, Falcao, Cerezo, Rivelino, have all disappeared. The midfield was divided between center midfielders who defended and center midfielders who played near the opponent’s penalty area, who dribbled and got forward, like Pelé and Zico. But the great thinkers disappeared. Like Xavi, like Iniesta, like Kroos… until today. The current Brazilian National Team has a Casemiro, who is a great player between the midfield to the goal, and a Neymar, who is a great player between the midfield to the goal. We are missing a great thinker. Over the last 30 years Brazil has not had a player that looks like Xavi. For this reason, Brazil’s game has stopped being a game of passes and has become a game of thrusts, without changes of direction. Without Rhythm. It reduced the collective game, the interchange of passes, the empathy, and the union that characterized Gerson, Rivelino, Clodoaldo, or Pelé who could play with everyone. Now we don’t develop players like this. And after 30 years, we are finally noticing.

Q. After passing, you said that the greatest virtue of Pelé was his aggressiveness.

A. All his qualities were at a superlative level. And where he had no rival was in his aggressiveness in the direction of the goal. He used both feet, used his head well… and he broke free with a lot of power. He was warlike, more than just a technician who could dribble and pass, which he did very well. When I ask myself what the difference is between Messi and Pelé, I think it’s the aggressiveness. Pelé was stronger physically. He added that warrior spirit to all his virtues. A fighter! He got mad when the opponent scored, when he was losing, and would catch fire and run back after the ball like he was a defender, looking for body contact and using his physicality to protect the ball and reach the goal. Players don’t always know how to use their physical strength. He was strong and knew he was strong.

Q. Against Uruguay you had two devastating passes that lead to goals, one for Clodoaldo and the other to Jairzinho. What goes into making this kind of legendary pass?

A. I was the top goal scorer for Cruzeiro but I was always a better passer than a scorer. I liked to filter decisive passes between the defenders. This was my gift. Enable the virtuous. Measure the small distances within closed defenses. For the goal that tied the game 1-1 vs Uruguay, when I received the ball in midfield, Clodoaldo yells to me, runs past, and the defender (who is Ancheta) goes with him in the direction of the goal. Ancheta sees me and stands between us. He is two meters ahead. If I think about passing it to Clodoaldo’s feet, Ancheta arrives sooner. So I play him the pass into space behind Ancheta so that the ball dies between Clodoaldo and the goalkeeper. Ancheta turned, unbalanced, and Clodoaldo scored. Two seconds elapse between Clodoaldo shouting at me and the ball reaching its destination. In that time I had to reason, measure the distance, calculate the positions of the bodies and send a reliable ball.

Q. Did Clodoaldo think a lot in the game or was he an intuitive center midfielder?

A. First off, he had enormous ability on the ball, something that was not common for a player in this position. He was not a strong scorer or combatative. He was not a Casemiro. But he was nimble and moved easily, he positioned himself very well, and he had a lot of ability to combine passes. The goal he scored against Uruguay to equalize at 1-1 was something unique in his career. He never set foot in the opposing penalty area. He wasn’t a player who arrived in the box. Not at Santos, not in the National Team.

Q. Brazil did not have a specialist defensive central midfielder?

A. Zagallo trained the collective positioning of the team every day; what to do every time we lost the ball, especially with Clodoaldo, Gerson, and Rivelino, who protected the centerbacks. If we lost the ball the three volantes had to retreat immediately back to the midfield. And after that we’d have to drop the attackers to help. None of them were great talents defensively, but those three positioned themselves very well and Gerson was the most intelligent organizer I have ever seen on the field. He had panoramic vision, played like he was seeing the field from a seat in the stands, and oriented with Clodoaldo and Rivelino about how to situate themselves defensively. He never stopped talking. Not on or off the field. The three complemented each other. Rivelino was the artist, the dribbler, the finisher, the one who shot from outside the area, the one who had incredible foot speed.

Q. What was your conversation with Gerson like before the final against Italy?

A. Italy marked man to man with a line of four that included a libero who stayed behind to cover, in case one of their defenders became overwhelmed in a 1v1. Gerson told this to Zagallo. Zagallo, who had been his coach at Botafogo, listened to him a lot. We planned two combinations. First, that Carlos Alberto would attack from the wing if Facchetti stayed with Jairzinho in the midfield and let himself be pulled diagonally from the right. This is how the fourth goal by Carlos Alberto was created. The second combination was that I would not drop down much to receive the ball and would wait between the libero (Pierluigi Cera) and the four defenders. By me not dropping down, the defender who had to mark me (Roberto Rosato) could not leave the penalty area. And Rosato didn’t leave. He didn’t cover on the fourth goal from Carlos Alberto, and he didn’t go out to cover Gerson when he dribbled and scored the goal to make it 2-1. Because he was marking me, I kept him from defending. The marked became the marker.

Q. To what extent does each team represent a moment in the life of their countries? Your generation was in primary school during the ‘50’s, during the New Republic, before the coup d’état in 1964. Did the performance of 1970 represent the Brazilian Republic?

A. In 1970, Brazil was a dictatorship. I hated the repression and the lack of liberty. A lot of people thought the same way. And this coincided with a generation of great footballers, the greatest artists, and the greatest musicians. It was the cultural splendor of Brazil. It is curious that an oppressive regime provoked a creative response in the people. Brazil never had so many extraordinary musicians. And the same happened in football. The National Team is not something that you can separate from the community. A lot of people who detested the dictatorship said that they would not root for Brazil, but once the World Cup started, everybody forgot that. I thought that we were living in a bad moment as a country, but this was a sporting competition. I had to separate those things. I was 23 years old. I was dreaming about success, of being champion of the world, of glory. We were ambitious. We wanted to demonstrate our worth. Like all Young people.

Q. Brazil 1970 is a standard of perfection. Was that a burden for successive generations?

A. Today when Brazil loses or plays bad, people repeat that we have to recover the essence of 1970. To play like we did in this era. But football changes. It’s not enough to want to return to the past. It’s not enough to want to play like 1970

Q. What changed?

A. There was a scientific development that combined with a technological evolution. It transformed soccer. The countries with better financial and social conditions, with better scientific preparation and academics in all areas, evolved more. Football evolved in Europe as a consequence of the evolution of life, of science, of technology, of public education. Primarily, they develop better coaches. In the ‘70’s Brazil, as well as the rest of South America, gradually sank into enormous poverty and social inequity. We have stayed behind. The deterioration of the formation of coaches and players reflects what is happening on the field. This is a really big country in which everyone likes football. That gives us strength, but the game went backwards. Even if we won the 2002 World Cup.

Q. What does scientific development have to do with football?

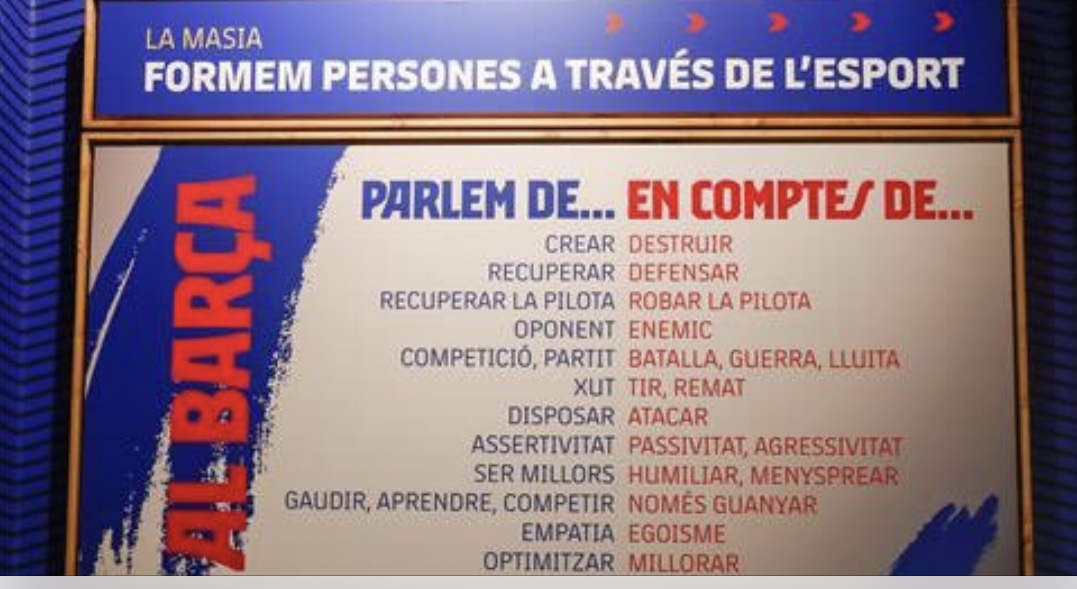

A. Since the ‘60’s, ability and fantasy were more important in the game. Brazil and Argentina were winning through their creativity and natural ability. That is very important in football, but the new scientific advances are becoming more decisive. It’s not just about ability. Brazil in the ‘70’s had various players at the maximum level. Today it has two or three. Or one. Our biggest crack is Neymar. And Neymar lives with problems, with confusions. We are not developing the spectacular players that we formed 40 years ago. We have lost the collective game of the midfield. Brazil lost that collective idea that motivates Barça, and has also lost its cracks.

Q. So the pass has been lost as a collective value because the sense of community has deteriorated?

A. There is a relationship. The pass is a symbol of the collective game and community life, of solidarity, of mutual respect. People totally have the right to want to improve their life, to enjoy its pleasures and earn money, but without forgetting that everyone else wants the same. Brazil created an egotistical society: where one part of society exploits the other. The sense of community has diminished in society, and the collective game has diminished on the field. Brazil plays an brilliant individual game. They play to score goals. Nobody plays for their team mate, nobody looks for an answer, nobody thinks about the organization. This is not the logic of the game, this is the logic of profit. We have more “ballers” than players who think about what they are doing. Dribble, dribble, dribble, shoot, shoot… It seems that we have very few players. Many get lost along the way. They come from a society that coexists with misery. What can you expect if half the population does not have potable water? It’s a shame! This is the fruit of the profit of others. Now football has turned into a game of individuals, not a team game. Because the country is an unequal country, in which some pursue winning at all cost and others lose everything. How can we ask footballers to not be individuals and think collectively? That is more tragic than the Pandemic.

.

Along the same vein as

Along the same vein as